Few creatures inspire awe quite like the owl, and at the heart of its silent hunts and unwavering perches lies a masterclass in biomechanical engineering: the musculature and tendons in owl limbs. These aren't just mere appendages; they are a finely tuned system, perfected over millennia, allowing owls to achieve their signature "locking grip" – a feat of strength and endurance that secures everything from a precarious branch to a struggling meal.

Forget what you think you know about bird legs. An owl's limbs are far more complex, lengthy, and vital than their often-hidden appearance suggests. They are the bedrock of an owl’s existence, powering everything from perching and walking to hunting, manipulating food, and even regulating body temperature.

At a Glance: The Marvel of Owl Limbs

- Hidden Length: Owl legs are surprisingly long, often concealed by dense plumage, with the true knee tucked high and unseen.

- Zygodactyl Mastery: Two toes forward, two back (with one highly rotatable), enabling a powerful, versatile grip.

- The Locking Grip: A unique flexor tendon mechanism allows owls to perch or hold prey without continuous muscle effort, conserving vital energy.

- Raw Power: Large owl species can exert 300-500 psi of crushing force, thanks to robust bones and mighty flexor muscles.

- Specialized Adaptations: From the thick, feathered legs of the Snowy Owl to the bare, rough-soled feet of the Fish Owl, limb structures vary wildly to suit diverse habitats and prey.

The Hidden Engineering Beneath the Feathers

When you observe an owl, its legs often appear short and stubby, barely visible beneath a thick coat of feathers. This is a clever optical illusion. In reality, an owl's legs are unusually long. Their femurs (thigh bones) are short and tucked high inside the body, close to the torso. What many mistake for a knee joint bending backward is actually the tarsometatarsus – the equivalent of our ankle and foot bones – connecting to highly elongated toes. The true knee is nestled high up, concealed by plumage, demonstrating how these birds essentially "walk on their toes."

This elongated structure provides leverage and reach, crucial for extending downward to snatch prey or grasping thick branches. The arrangement keeps the bulk of the powerful leg muscles closer to the body, centralizing weight for better balance and aerodynamic efficiency.

Talons and Toes: The Anatomy of a Lethal Grip

An owl's foot is a precision instrument, designed for capture and control. Each foot boasts four digits, each tipped with a formidable, sharply curved, and lengthy talon made of keratin. These talons aren't just sharp; they are the primary tools for the hunt, capable of delivering crushing constriction, decisive stabbing, or even severing the spine of their prey.

What makes the owl's grip so special is its zygodactyl foot structure. Unlike many birds with three toes forward and one back, owls typically present two toes forward and two backward. Crucially, the outer front toe is incredibly flexible and can rotate backward at will. This allows the owl to switch between a two-forward/two-backward configuration for perching and a three-forward/one-backward arrangement for a more powerful, spread-out grip on prey or a wider purchase on a branch. This variable setup enables them to spread their talons wide, creating a large capture net for unsuspecting victims.

The underside of an owl's digits isn't smooth; it's rough and lumpy, providing exceptional traction. Fishing owls, for instance, take this to another level with exceptionally rough soles, perfectly adapted for gripping slippery fish. Some species, like the Barn Owl, even feature a serrated edge on the underside of their middle toe, a handy comb for grooming feathers and aiding in subduing struggling prey.

The Locking Grip: Tendons That Defy Fatigue

Here's where the musculature and tendons in owl limbs truly shine. Imagine holding onto a branch all night, or clinching a struggling rodent for an extended period, without your muscles ever tiring. Owls manage this through a unique physiological marvel: the flexor tendon locking mechanism.

This isn't a conscious effort; it's an elegant anatomical design. When an owl perches or grasps prey, the weight of its body or the pressure on its feet automatically tightens the flexor tendons that run along the back of its lower leg and into its toes. These tendons engage with specialized ridges on the bone, creating a "lock." This mechanism allows the owl to grip tightly without expending continuous muscle energy, effectively "locking" its toes in position.

The benefits are profound:

- Energy Conservation: Owls can perch for hours, even sleep, without falling or constantly engaging their muscles.

- Unwavering Hold: Once prey is caught, the locking grip ensures it can't escape easily, freeing the owl's focus for other tasks.

This ingenious system is a prime example of evolutionary efficiency, allowing owls to be patient hunters and tireless sentinels.

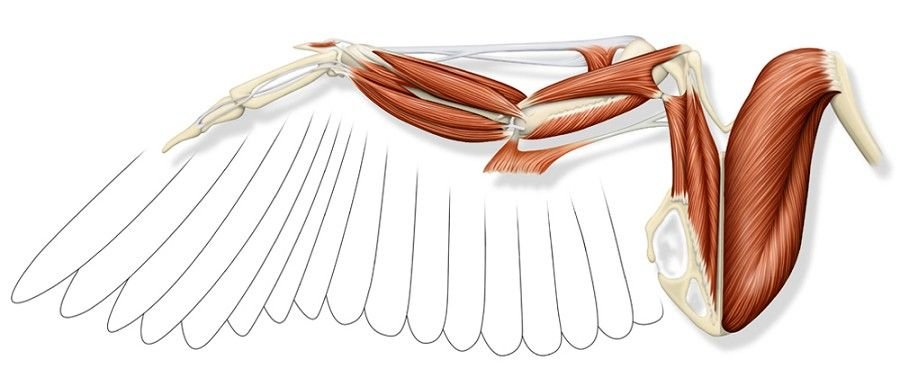

Built for Power: The Muscular Might of Owl Legs

While the locking mechanism is about efficiency, the underlying strength comes from robust musculature and bones. The entire owl foot is highly muscular, particularly the flexor muscles responsible for closing the grip. These muscles, combined with thick, strong tendons and dense bones, allow owls to exert incredible force.

Large owl species, such as the Great Horned Owl or the Eurasian Eagle Owl, are known for their formidable strength, capable of delivering a crushing force of 300–500 pounds per square inch (psi). To put that in perspective, that's roughly equivalent to the bite force of a large dog, but concentrated into four razor-sharp points. This raw power, coupled with the locking mechanism, makes their grip truly inescapable for most prey.

Aerial Agility: Legs in Flight and Balance

An owl's legs aren't just for perching and pouncing; they're integral to its legendary silent flight and aerial balance. The architecture of their limbs supports their lifestyle:

- Centralized Weight: The larger, more muscular upper leg segments are kept compact and close to the owl's body. This centralized weight distribution improves flight stability and maneuverability, reducing the energy cost of carrying heavy muscles far from the body's center of gravity.

- Light Lower Legs: The lower legs, comprising the tarsometatarsus and toes, are relatively light, made up mostly of bone and tendon rather than bulky muscle. This minimizes destabilizing weight at the extremities during flight.

- Aerodynamic Tuck: In flight, owls tuck their long legs tightly against their body, streamlining their profile for optimal aerodynamics. The feathers on their legs blend seamlessly with their body plumage, further reducing turbulence and absorbing sound, contributing to their famously silent flight.

Keeping Cool (or Warm): Temperature Regulation via the Limbs

Beyond their roles in locomotion and hunting, owl legs play a surprising role in temperature regulation, a critical function for survival in diverse climates.

- Heat Radiation: The soles of an owl's feet are equipped with extra blood vessels. When an owl needs to shed excess body heat, blood flow to these vessels increases, allowing heat to radiate away from the body. You might observe an owl panting and extending its feet on a hot day, using its soles like radiators.

- Insulation: Feathering on the legs and feet also acts as a vital thermostat.

- Snowy Owls, native to the Arctic, possess exceptionally thick feathering that extends all the way down to their talons. This dense insulation is crucial for preventing frostbite and retaining body heat in brutally cold environments, allowing them to hunt effectively in snow and ice.

- In contrast, Burrowing Owls and Fish Owls have light or even entirely unfeathered legs. Burrowing Owls, inhabiting arid regions, benefit from bare legs that can dissipate heat more easily. Male Burrowing Owls, in particular, have less leg feathering than females, a likely adaptation for their active roles in digging and maintaining burrows. Fish Owls, which spend time standing in water, keep their legs minimally feathered to prevent them from becoming waterlogged, ensuring their plumage remains dry and insulating.

Masters of Adaptation: Species-Specific Leg Designs

The fundamental design of musculature and tendons in owl limbs is highly adaptable, allowing different owl species to thrive in distinct ecological niches. Each species showcases specialized features that optimize their hunting strategies and habitats:

- Burrowing Owls: Proportionally, these owls have the longest legs among their kin, coupled with light feathering. This adaptation suits their largely ground-based lifestyle, enabling them to run, walk, and jump efficiently while hunting ground invertebrates (a significant portion of their diet) and maintaining their extensive burrows.

- Forest Owls: Species that inhabit dense woodlands, like the Barred Owl, tend to have shorter legs. This shorter length provides better maneuverability and reduces the risk of entanglement in thick vegetation, allowing them to navigate cluttered environments with ease.

- Snowy Owls: These Arctic predators possess exceptionally powerful, thickly feathered legs. This robust build provides not only vital insulation against extreme cold but also the sheer strength required to capture large, powerful prey such as Arctic hares and ptarmigans.

- Barn Owls: Known for their elegant, silent flight, Barn Owls feature long, slender, and lightly feathered legs. These are perfectly adapted for reaching down into tall grasses to grab rodents, and their highly flexible toe rotation helps them secure a precise grip. They generally boast the longest legs relative to their body size, a characteristic that aids their specific hunting style.

- Great Horned Owls: These formidable hunters exhibit extremely muscular, fully feathered legs. Their impressive strength and one of the strongest grips in the avian world allow them to successfully capture diverse and often large prey, including rabbits, skunks, and even other birds of prey.

- Fish Owls (e.g., Blakiston’s Fish Owl): A true specialist, the Fish Owl has large, unfeathered toes equipped with uniquely rough soles. These adaptations are crucial for grabbing slippery fish from water, while their strong, thick legs allow them to stand patiently in streams or rivers. You can explore more about these incredible adaptations in Your guide to leg owls.

- Eurasian Eagle Owls: Among the largest and most powerful owls, Eurasian Eagle Owls are characterized by their thick, heavily muscular legs and huge talons. This formidable combination enables them to take down prey as large as foxes and small deer.

Beyond the Catch: Feet as Tools and for Growth

An owl's feet aren't solely for hunting and perching. They serve other vital functions:

- Manipulation: Owls use their feet much like we use our hands. They will often grip and manipulate food, tearing off bite-sized pieces and guiding them to their bill. This dexterity allows them to process prey efficiently.

- Owlet Development: Baby owls, or owlets, are born with surprisingly large feet relative to their body size. Their talons are soft at birth but rapidly harden and grow. The quick development of their leg musculature and tendons is crucial, as a strong grip is a fundamental survival skill they must master early.

Unraveling the Secrets: How Scientists Study Owl Limbs

Our understanding of the intricate musculature and tendons in owl limbs has grown significantly thanks to modern scientific techniques. Researchers employ a variety of methods to study these fascinating structures:

- X-rays and CT Scans: Provide detailed insights into bone structure, joint articulation, and the precise arrangement of tendons.

- High-Speed Photography: Captures the dynamic movements of owls in flight, during a strike, or while perching, revealing the exact mechanics of their toe rotation and grip.

- Pressure Sensors: Integrated into artificial perches or experimental setups, these sensors measure the incredible crushing force owls can exert.

- Owl Pellet Analysis: While not directly studying the limbs, examining owl pellets (undigested fur and bones) helps scientists understand an owl's diet, indirectly informing us about the type of prey its feet are adapted to handle.

- Comparative Anatomy: By comparing owl limb structures to those of other raptors and birds, scientists gain a deeper understanding of the evolutionary pressures that shaped these specialized adaptations.

The Ever-Evolving Owl: A Testament to Nature's Design

The intricate interplay of musculature, tendons, and specialized bone structures in an owl's limbs is a profound testament to natural selection. From the energy-saving locking grip to the species-specific adaptations for diverse prey and climates, every element is a finely tuned component in a perfectly engineered system.

Next time you see an owl, whether perched stoically on a branch or swooping silently through the night, take a moment to appreciate the hidden power and precision within its limbs. It’s a marvel of evolution, a living example of how nature crafts the perfect tool for every purpose. These remarkable adaptations are not just fascinating; they are critical to the owl's survival and its enduring reign as a master hunter of the night.